I was conflicted regarding whether or not to write about COVID-19, because I myself have become weary of the constant stream of pandemic-related media. Yet, as I sit at home and watch the historic moments roll by like tumbleweeds outside my window, I find myself with many thoughts and few places to put them. I find myself thinking, in fact, about a head of lettuce.

Nearly three years ago, I was working as an administrative assistant at St. Margaret’s Episcopal Church. The rector, Fr. Rob, and I were out buying supplies for a barbecue. As he scoured the aisles for ketchup, he told me to go pick out a head of lettuce. I found the perfect one—crisp, green, and generous. I grabbed a plastic bag from the nearest roll and tried to put it in. Reader, that head of lettuce would not fit into that bag. I struggled. I stretched. I heaved a sigh of righteous indignation. Soon enough, Fr. Rob came over to me, and I demonstrated the problem.

“That one won’t fit,” he said frankly.

“Yes,” I replied.

“Well, try another one,” he suggested.

I gave him a bewildered look as he took the perfect head of lettuce out of my hand, replacing it with a smaller one, which easily slid into the bag.

“There’s a sermon in that,” he said with a smile, and walked ahead of me to the checkout.

I hold to this day that my indignance was appropriate. I did exactly what I was supposed to do. I picked well from the produce presented to me, and was betrayed by the packaging system implemented by the purveyors of that very same produce. That is not how it’s supposed to work. And yet, Fr. Rob’s solution panned out just fine—shockingly, no one at the barbecue complained about the quality of the lettuce.

In the long run, the store needs to get bigger bags rather than force its customers to choose smaller lettuce. The problem is fixable, and should be fixed. In the moment, though, Fr. Rob accepted the imperfection and found a simple way to meet our need. He didn’t get hung up, as I did, on how it was supposed to be.

Right now, almost nothing is how it is supposed to be. We’ve hit upon more than a few imperfections in our global, national, and local systems, not to mention in ourselves. We must remember and learn from these imperfections. After all, our word “apocalypse” comes from the ancient Greek for “uncovering” or “revelation”—the worst of times forces us to face problems that have been there all along. This pandemic has shown us the need for transformation in our world.

And yet, if we get too hung up on how things should be in this moment of crisis, we may be left holding the bag. Stewing in our sense of what is fair, especially what is fair to us, is no more helpful than staring at an oversized head of lettuce. Some righteous indignation comes from love of others; this dynamic care is what will move us to mend what we now find broken. Head-of-lettuce indignation, however, that which centers on the self and what we are owed, is not moving but paralyzing.

One head of lettuce I’ve held too tightly since I can remember is that of grades—an academic system of measurements which is supposed to be consistent and fair. I so relished the idea of being objectively assessed and placed on a comprehensible scale that I assigned myself homework in preschool. This system is supposed to give us exactly what we deserve, and we are supposed to be able to work hard enough to be deserving. We are supposed to be able to fit.

In response to the variable and adverse circumstances imposed on students by this pandemic, the faculty and administration of my school, Pomona College, implemented a new grading system for the semester. Instead of the almighty letters to which we are accustomed, we may be assigned either a Pass or Incomplete.

As you can imagine, the question of grading has been incredibly controversial among students. While I had the privilege of returning to a good home, equipped with quiet spaces and WiFi, many of my classmates did not. Many of them are in the impossible bind of trying to perform well academically without the proper resources to do so, and even having to support and care for family members. Ultimately, the administration felt that having letter grades as an option would put them at an even deeper comparative disadvantage. Yet, many students, some of them in extremely adverse situations themselves, wanted the choice to keep the grades they had already spent almost two months earning. They wanted their transcripts to reflect what they had worked for. They wanted the system to fit their reasonable expectations, live up to the way it was supposed to be.

It doesn’t, and it can’t. Our solutions are imperfect. Often, there is simply no way for everyone to win, no bag big enough for the lettuce we so carefully choose. To vastly varying degrees, we are all making sacrifices we didn’t sign up for. We are called to dig deep, find the grace to pick the smaller self, the smaller life, the smaller lettuce.

There is a shocking beauty to the Pass/Incomplete system in which I find myself. In this grading scheme as in life, we don’t get exactly what we deserve, good or bad. If I throw myself into my work and earn an A, I won’t be rewarded with a shinier transcript. If I put in as little effort as possible and skate by with a C, I won’t be punished with a lower GPA. In either circumstance, I will simply pass. If somehow, despite my extremely privileged circumstances, I manage to fall short even of that standard, I won’t get what I deserve—to fail. Instead, I’ll get the mercy of a second chance—the Incomplete.

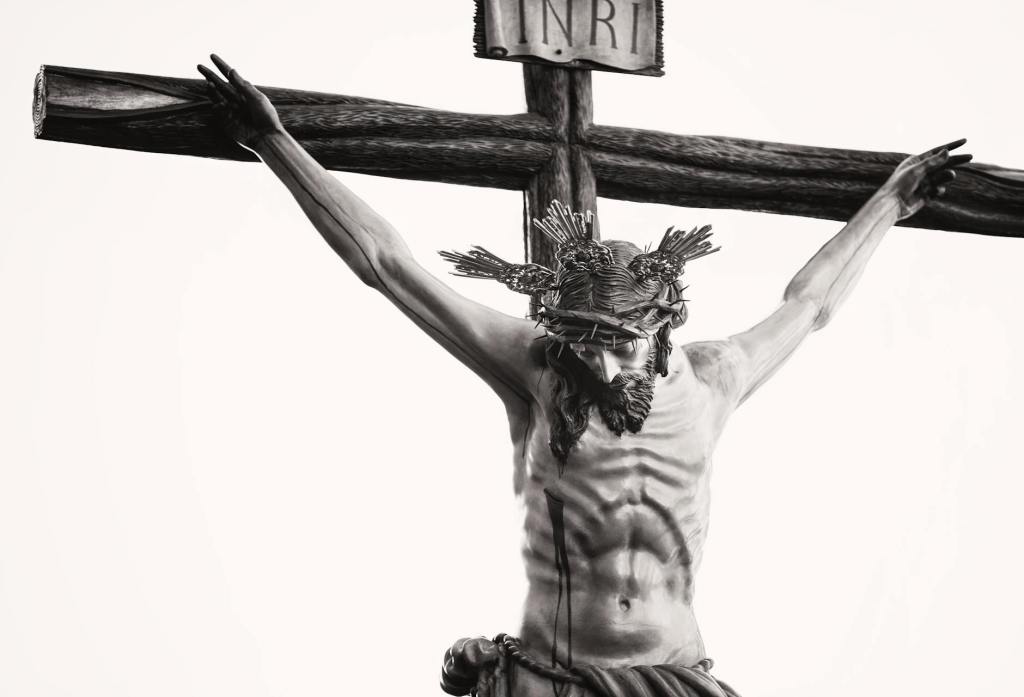

I would like to think that the grace of God works something like this. The parable of the laborers in the field makes clear to us that there is no place for self-righteousness in heaven; even the latecomers get a full day’s wage. The saint and the sinner both are saved by one and the same crucified, living God. This is not to say that there is no benefit to striving for saintliness. I am blessed with the resources and opportunity to spend time on my school work even during this pandemic, and if I do so, my life may be enriched by what I learn. Similarly, when we take the opportunity to grow in faith and love, our souls may find more joy in our lifelong labor. The only thing stopping us from reveling in that fact is our sense of fairness, of deservingness, of how things should be.

And perhaps, with God, there is no Fail—only Incomplete. Indeed, ours is the God of seventy-times-seventh chances. This God surely seeks every lost lamb, desires for every prodigal child to come home, runs to embrace us before we can even choke out our apology. Yet, this is also the God of the wanderer, the questioner, the voice crying out in the desolate places of the earth. This is the God of the stage-frightened speaker, the prince-turned-vagabond, who never makes it to the Promised Land. This is the God who so loved the world as to pitch a tent among us. Perhaps even when we feel all is lost, when we’ve fallen short of even the most generous mark, we are not condemned but given the space to keep going.

All in all, this is a hard time to go grocery shopping. We are unlikely to find just what we came looking for. Nothing and no one is where it’s supposed to be. Nothing is meeting our reasonable expectations. As we live through and beyond this, we must make good use of the revelations unfolding before our eyes. We must strive for a just world. But we will never have a fair one. A fair world would only be to the detriment of a human family sorely in need of grace. And, after all, fairness isn’t usually how we meet our needs and those of the community. It isn’t how we’ll meet the needs of a world in pain. Our love and care and zeal and righteousness only reach their potential when we put down our personal “supposed to”—and pick up a smaller head of lettuce.