This post is the third in a poorly spaced-out series on the Holy Spirit in 1 John and the Farewell Discourse. So far, we have discussed the boringness of my master’s thesis, the unfortunate scholarly implication that 1 John is boring too, and the crystal clarity of undying, willing-to-die love in Jesus’s final teachings. Now, we move to the crossover between the Discourse and the epistle, which I contend will begin to demonstrate how electrifying the latter truly is.

Upon reading John 13-17, we find several words repeated like a drumbeat: Father, Son, Spirit, commandment, truth, completeness, love, abiding. 1 John is interested in the same things: who is God? What does God command? How can we understand the truth? How can our community be whole and joyful? The epistle leads its readers to one Being as the locus of mystery and faith. It leads to the Spirit of abiding love.

In 1 John 3:11-24, the author expounds upon the primacy and true meaning of love. It can hardly be a coincidence that this passage contains overlap with the Farewell Discourse, is laden with language of abiding, and culminates in the Epistle’s first explicit reference to the Spirit.

Echoing the notion of tangible revelation found in 1 John 1:1—“We declare to you what was from the beginning, what we have heard, what we have seen with our eyes, what we have looked at and touched with our hands, concerning the word of life”—and the proclamation of gratitude, awe and confidence of verse 3:1—”See what love the Father has given us, that we should be called children of God; and that is what we are”—verse 3:11 begins, “For this is the message you have heard from the beginning, that we should love one another.”

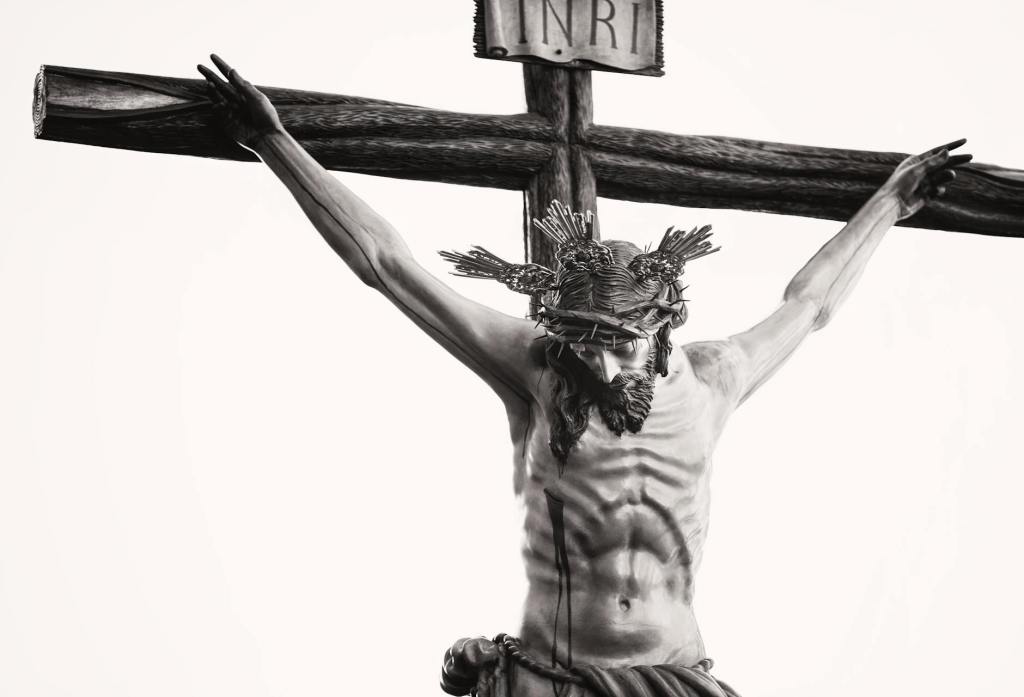

Reading these verses together and in the context of what the latter has taught so far, we begin to move toward the identification of God with love. Christ, God Incarnate, who “emptied himself, taking the form of a slave” and was “obedient to the point of death— even death on a cross” (Philippians 2:7-8), is Himself “what was from the beginning” (1 John 1:1; cf. John 1:1). Christ is the Word, the Message. Yet, in 1 John 3:11, communal love is said to be the original message. Real, touchable, flesh-and-blood Jesus and real, active, meet-your-neighbors’-needs love are inseparable. As we saw in the Farewell Discourse, to love is to be with Christ.

1 John 3:16 represents a more exact overlap between the texts: “We know love by this, that he laid down his life for us—and we ought to lay down our lives for one another.” John 15:13 uses the image of laying down one’s life to represent the highest form of love (see also 13:34-38); here, the author of the Epistle uses the same language to describe Christ’s actions for the believers, then expands this to an ideal for their community. The Epistle does what the Farewell Discourse, set before the crucifixion, cannot: it explicitly defines the love in terms of Christ’s crucified flesh and blood.

So far, the letter has been insisting that the meaning of the Gospel is not just ethereal, flowing whispers in the wind. It is not just feeling and mysticism, as the secessionists may have claimed. The Gospel hinges on the fact that God became incarnate through a young unmarried woman, walked around in Nazareth, ate, drank, washed the dust off of his friends’ feet, died a real and horrific death, and rose again. Our response to the Gospel must be a kind of love that is visible in our incarnate—i.e., embodied—behavior. Far from being nonphysical, this love is so embodied that its ultimate expression is sacrifice of the body. Yet, for the author of 1 John, radical tangibility and radical pneumatology go hand-in-hand.

The last verse of this passage, 1 John 3:24, is key: “All who obey his commandments abide in him, and he abides in them. And by this we know that he abides in us, by the Spirit that he has given us.” As we know from earlier in this chapter and from the Farewell Discourse, obeying God’s commandments means loving one another tangibly and loving the incarnate God. Thus, again, to love is to be with Christ—in this case, to have the Divine abiding with us, even in the absence of the visible Christ. And how do we know that God is dwelling, remaining, abiding with those who love? By the gift of the Spirit.

Somewhat counterintuitively, the epistle offers the intangible as assurance of the tangible. The Spirit is proof that the incarnate God of love sees our incarnate human love and responds. “See what love the Father has given us” indeed: the Spirit of abiding love.

This letter contains more than its share of indictments and imperatives, but above all, it is a letter of assurance. This will become even more apparent in chapter 4, as will the connection between love, abiding, and the Spirit. However, for today, this fourth Sunday of Advent, it is appropriate to emphasize the comfort found in chapter 3.

We worship a God who not only created us, but chose to participate fully in our world even though—indeed, because!—our selfishness had broken it. Our flesh, fragile though it may be, is sanctified by that enfleshment. Our bodies are not bad. Our hearts are not irreparable, yet neither do they have the final word: when we feel insufficient, when we hate ourselves, God’s love overcomes us and makes us capable of love (1 John 3:18-20). And though we try, in manifold ways, to kill Christ, he continues to come to us, year after year, as a vulnerable infant, a longed-for savior, loving us perfectly, determined to abide.

Leave a reply to revjanholland Cancel reply